In the Chūbu region of which Owari was the center, Takeda Karakuri are preserved in the form of parade floats. This differs from Kyoto, Osaka, and Edo. In this region, interest in the different types of Karakuri dolls was the prevailing force behind development of the dolls. For this reason, a number of different types of Karakuri dolls can be glimpsed on top of the floats featured in local festivals.

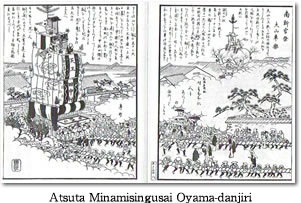

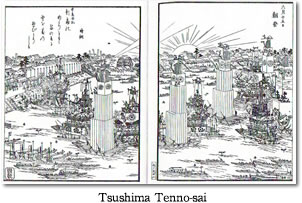

Float parades or dashi matsuri are thought to have originated at Kyoto's Gion Festival in 896 CE. Parades featuring yamaboko-style floats like those seen in the Gion Festival subsequently spread throughout the country. Dolls served as representatives of the gods on some of the Gion Festival floats, but the first parade featuring floats with moving Karakuri-style dolls is thought to have been the Atsuta Shrine Tennō-sai (1469-1486) held in medieval Owari or the Tsushimashi Tennō-sai (1435-6, oldest record of doll usage 1522).

Knowledge of Karakuri dolls spread through spectacles such as the Takeda Karakuri Theater, leading to advances in the internal mechanisms used in the dolls. Festivals began featuring Karakuri performances in which the dolls' movements were synchronized to music. The years between the early and middle Edo period thus witnessed the birth of festival dolls or Dashi Karakuri.

In a move to restructure the finances of the shogunate, the eighth generation shogun Yoshimune (1716-1745) set forth a strict set of regulations limiting expenditures and forcing the common people to endure a number of hardships. One of the new regulations was the so-called Shinki Hatto no O-Furegaki, which banned the manufacture of new machines and textiles as part of a general prohibition on luxury goods. This proved a great hindrance to the development of technology.

However, technology used in spectacles and other forms of entertainment was specifically exempted from this ban in the text of the edict. The pleasures of the common people were not targeted by the government.

Against this historical background, the seventh generation daimyo of the Owari clan, Tokugawa Muneharu, enacted a new government policy of “enjoying the world with the common people” in 1730 which promoted festivals and other forms of amusement. This led many craftsmen to settle in Nagoya, the capital of Owari Province. Tamaya Shobei, a Karakuri doll craftsman from Kyoto, was one of these.

The history of Tamaya Shobei dates to 1734, when the first generation of the family moved to Nagoya and began manufacturing and repairing Karakuri dolls used in festivals. Today the ninth generation Tamaya Shobei continues this work.

Festivals featuring Karakuri float parades became very extravagant during this period, for example, the festival held in honor of Tokugawa Ieyasu at Toshōgū Shrine. Float makers competed to create the most technologically sophisticated Karakuri dolls.

Nagoya was the center of the Owari clan's political influence and was considered the Tokugawa family's stronghold. The forests and mountains of the Kiso region to the north, Ise Bay to the south, and Mikawa Bay were all under Tokugawa control. It was also a hub on the Tōkaido Highway linking Edo and Kyoto, one of the most important information corridors in the country. The above factors plus the economic clout represented by the grain-producing Nōbi Plain region and the pro-festival policies of the Muneharu-led Owari clan helped spur the rapid development of Karakuri parade float culture. This prosperity permitted numerous communities to possess Karakuri dolls, which represented a considerable luxury at the time. In addition to Karakuri dolls, craftsmen competed to create the most extravagant curtains and sculptures for parade floats. This trend reaching its height in the late Edo period.

Even in Owari Nagoya, however, the development of Karakuri floats was hindered by the restrictions set forth in the Shinki Hatto no O-Furegaki edict. In Kōriki Tanenobu's Enkōan Diary, there is an entry from June 1802 which reads, “June 13th: Nishibiwajima Rokken-chō festival will begin using floats this year. However, they will be placed in front of the shrine as decorations and plans for a parade procession have been postponed. This is due to a mandate from the government office. [...] dolls will not be permitted in the festival.” Ten years later in June of 1812, “Dolls will be permitted in the Nishibiwajima festival to be held on the 11th, but Karakuri dolls are not yet ready.” Starting with the next year's festival, “Parade floats in the Nishibiwajima festival have been granted permission to use Karakuri dolls for the first time this year.” Thus even the powerful Owari clan was very circumspect in its treatment of Karakuri, due to the association of these dolls with advanced technology.

In the Mino region, formerly a part of Owari Province and now located primarily in modern-day Gifu Prefecture, festivals featuring Karakuri doll floats became the norm during the Edo period. Over 200 of these floats are still in existence today. This means that over 80% of the Karakuri floats in existence in Japan are located in the prefectures of Aichi and Gifu.

Over 300 floats are used in more than 50 festivals across Aichi Prefecture, with roughly 120 of these floats featuring Karakuri dolls. More than 300 of these dolls are currently in use. This makes Aichi Prefecture a veritable treasure trove of parade float Karakuri dolls.

Even from a global perspective, examples like this of the continued use of original 18th-century machine technology are rare.